International Blasphemy Day 2013 – Varieties of Blasphemy

The concept of “blasphemy” remains a huge problem faced by atheists, other non-religious people, and religious minorities around the world.

On the one hand, “blasphemy” is simply what you call it when someone is irreverent or insulting about religion. However, the word is deeply entwined with the idea of moral outrage and criminal offence. “Blasphemy” is rarely used merely to describe ideas that someone finds offensive in relation to the divine (as they see it); rather it is used to target views that the speaker wants to see shunned, outlawed, prohibited, censored.

Blasphemy laws and the accusations made under them must make use of religious offence; they must appeal to those who are angered by hearing criticism or ridicule of their beliefs. But in many cases there is often another motivation alongside the charge. I’ll consider three below.

Scapegoating or inciting hatred against minorities

Rimsha Masih, a girl from a Pakistani Christian background, was accused of burning the Qu’ran by Khalid Chishti, a Muslim cleric. Chisti was on record agitating against the Christians in Islamabad and looking for excuses to malign them. Here the charge is brought privately and the authorities go with the grain of the blasphemy law, quite possibly cognisant that those in power who resist blasphemy laws are themselves under threat of assassination. (In Rimsha’s widely-reported and unusual case, she was eventually released and a case pursued against Chishti – however the witnesses who accused him of planting evidence against the girl later withdrew their testimonies.)

Alexander Aan, jailed for two and a half years over an atheist group on Facebook

In some cases the authorities appear to pursue blasphemy accusations in order to create a social scapegoat out of a minority. Indonesia is known for its systematic ongoing violations of freedom of religion or belief. Alexander Aan, in another case featured in the 2012 Freedom of Thought report, is still in jail today for comments made on an atheist Facebook page, criticising Islam and stating that he had left Islam to become an atheist. He was also charged with false reporting on an official form for stating that he was a Muslim when in fact he was an atheist, despite the fact that stating ‘atheist’ on the form is itself prohibited by law! He was ultimately sentenced to two and a half years in prison for “spreading information inciting religious hatred and animosity”.

This is clearly an example in which Aan (who cannot reasonably be said to have done anything even malicious, let alone inciting hatred or violence) was scapegoated. But it’s also a case where there are clearly elements of enforcing social conformity by making an example, too. Whereas Rimsha Masih may have been targeted more to agitate against an existing community, Aan was made an example of to deter the potential non-religious minority from speaking out. His “crime” was daring to speak outside the bounds of socially acceptable and sanctioned views, his punitive punishment a kind of warning to others.

Dressing up political suppression with a populist charge

Blasphemy accusations are often used to target individuals who have expressed other social and political views (for whom religious criticism may be an insignificant part of their overall output) with an accusation that finds populist support. If the population is used to accepting ‘blasphemy’ as a valid charge and is afraid to criticise it for fear of themselves being targeted, then ‘blasphemy’ is a safer way of targeting someone with politically inconvenient views. The recent case of Aleksandr Kharlamov in Kazakhstan, which will appear in the 2013 Freedom of Thought report, is such a case where the accused’s writing (including some texts which may not even have been published but were seized from a home computer) are used to punish him for his political activism, in this case against corruption. His case study from the upcoming Freedom of Thought report (subject to change) should be revealing:

On March 14, 2013, atheist writer and anti-corruption campaigner Aleksandr Kharlamov was arrested for “inciting religious hatred”. The indictment against him claimed that Kharlamov “in his articles on newspapers and the internet put his personal opinions above the opinions and faith of the majority of the public and thus incited religious animosity”. In a step reminiscent of Soviet-era abuses of the psychiatric system, Kharlamov was confined to a psychiatric hospital for “psychiatric evaluation” of his opinions and writings on religion. Kharlamov reportedly lost 20 kgs during just the first three months of his incarceration. He faces up to seven years in prison if convicted.

Kharlamov has been released on bail but a trial is still pending while his writing awaits so-called “expert analysis” by the authorities.

Other high profile cases which may fall into a similar category this year include Turkish pianist Fazil Say, who is well-known for his atheism, but also for his leftist and secularist opposition to the current government.

Raef Badawi jailed for 7 years and sentenced to 600 lashes for running a liberal blog

The horrific case in Saudi Arabia of Raef Badawi — at IHEU we called his punishment of 600 lashes and 7 years in jail a “gratuitous, violent sentence” — also clearly falls into this category. He was charged with “ridiculing Islamic religious figures”, and “going beyond the realm of obedience” as well as “setting up a website that undermines general security”. The website was simply a liberal blogging network calling for, among other things, freedom of thought and expression, and may have included criticism of some religious leaders (the site was ordered taken down during sentencing because it “violates Islamic values and propagates liberal thought”). Badawi’s case illuminates how bound up the political and the religious motivations behind ‘blasphemy’ can be. There is no clear dividing line here between criticism of religious fundamentalism or particular religious authorities and ideas which supposedly threaten state “security” simply because they express new and more liberal political ideas. But is is convenient to state the charges in terms of religion when oppressive ‘blasphemy’ laws and populist righteous anger are on you side.

Placating or courting a religious lobby

Charging someone with “blasphemy” may be seen as a convenient easy win for a government that is trying to tout its religious credentials to fundamentalist or other hardline religious groups. In addition it may be seem like a quick way of placating an agitated, politicised religious lobby.

Islamists protest in Dhaka calling for the death of atheist bloggers

This is certainly what we have seen this year in Bangladesh. Islamist groups angered by war crimes trials against some of their leaders lashed out at the organisers of protests calling for justice by claiming that the “atheist bloggers” involved should be put to death. Already earlier in the year one such blogger, Ahmed Rajib Haider, had been attacked and killed. Instead of telling the Islamists where to go, the government responded by taking the Islamists’ concerns seriously, accepting a “list” of 84 bloggers the Islamists demanded should be investigated, and Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina responded that no new blasphemy law was needed only because existing laws against “inciting hatred” would be enough to prosecute them. Four bloggers including Asif Mohiuddin – simply for blogging about their politics and in some cases their atheism – have now been awaiting trial since April which could see them receive multi-year sentences under existing legislation.

The ruling Awami League party is not Islamist, but the pursuit of the bloggers looks a lot like placating the Islamist lobby. Not only is this worrying in itself, it also doesn’t work. At IHEU we warned that giving any ground over the supposedly ‘blasphemy’ allegations would be “walking into a trap set by fundamentalists”. And sure enough the list of demands was then followed up by a march of 100,000 Islamists (at the lower estimate) demanding among other things that the bloggers be executed and that new Islamist clauses should be inserted into the country’s constitution.

“Use and misuse” of blasphemy laws

Whether motivated by a searing, reactionary compulsion to stamp out criticism and ridicule of religion, or employed cynically to prosecute people for political gain or to marginalise minorities, laws which prohibit blasphemy are never a social good, always a social ill. All prosecuted supposed expressions of ‘blasphemy’ seem to fall into one of a few kinds:

- simple statements of non-belief

- statements critical of religious beliefs, practices or authorities

- symbolic acts or artworks implying criticism or resentment of religion (often these are a source of false accusations, as with the framing of Rimsha Masih and many others for supposedly “desecrating the Qu’ran” – an accusation which has become a kind of magic command to unleash mob justice in Pakistan)

- satire or ridicule of religion

Laudably the new EU Guidelines on Religion or Belief explicitly note that statements which “ridicule” religion are not thereby incitement to hatred or violence and are protected under international rights law. They also explain that the possibility of resulting violence (i.e. if those who are offending turn violent in the backlash) is not the same as inciting violence against anyone or from those people.

Indeed none of the above modes of ‘blasphemy’ is sufficient on its own to constitute genuine incitement.

Blasphemy laws always by their nature prohibit more varieties of thought, action and expression than would legislation which targeted genuine hate speech or incitement.

Some critics of blasphemy laws campaign against their misuse or abuse. This may be appear a strategic necessity in a country like Pakistan or Indonesia or Saudi Arabia, where curbing the worst excesses of ‘blasphemy’ prosecutions is a priority. But it does not go far enough as a response by the international community to ‘blasphemy’ prohibitions. Blasphemy laws are not “misused” or “abused” when they result in clear injustice against religious critics etc, or in violations of fundamental rights. That is how blasphemy accusations are used when they are used “correctly” in accordance with (bad) law. And very often that was the intention underlying the establishment of those laws in the first place.

Giving blasphemers a voice

Today was declared International Blasphemy Day by CFI a few years ago, after the Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons furore. They’ll be interviewing two victims of blasphemy today (4pm EST, or 8pm GMT) giving Alber Saber from Egypt and Kacem El Ghazzali from Morocco a chance to speak about their mistreatment at the hands of blasphemy laws.

Kacem has also spoken for IHEU as our representative at the United Nations in Geneva since fleeing to Europe, on one occasion asking the Moroccan delegation directly “Why must I be killed?” We also republished a blog by one of the jailed Bangaldeshi bloggers, Asif Mohiuddin, in June.

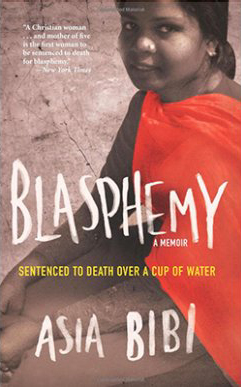

In a new book, Blasphemy, French journalist Anne-Isabelle Tollet has given voice to Asia Bibi, jailed in Pakistan since she was maliciously accused of “blasphemy” in 2009 and sentenced to death in 2010. She is still in jail today.

It goes to show that while absurd jail sentences, vicious corporal and even capital sentences, and mob justice continue, there is mounting international pressure to abolish blasphemy laws wherever they are established, and a new drive toward hearing accused “blasphemers” in their own words. As long as there are blasphemy laws, we will continue to document, campaign for and moreover to give voice to the accused.