Foreword

Foreword to the 2024 edition

Leena Manimekalai – Photo Credit Michael Miroshnik

By Leena Manimekalai, award-winning Indian poet and filmmaker

‘A Trial by Fire’

In December 2021, when I received word that my submission to the i am…project’s call for proposals1 had been selected as part of Toronto Metropolitan University’s “Under the Tent”2 cohort of graduate students from universities across Canada, I was elated. Though it wasn’t meant to bring me either credits or grades, I was excited to be part of an academic research project that would take me beyond my own master’s course in Film at York University.

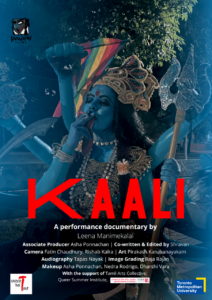

Exactly seven months later, on 2 July 2022, I finally had an opportunity to share the creative piece that I had spent the duration of the program developing, in an exhibition at the Aga Khan Museum for Canada Day celebrations. The performance documentary short, Kaali, is a film-meditation on the themes of being, becoming and belonging in the city of Tkaronto.3 In the film, I embodied the Indian goddess Kali, whose roots lie in the Indigenous and caste-oppressed communities of the Indian subcontinent,4 and wandered the streets of downtown Tkaranto to evoke the reactions of people from all walks of life. Along with a pride flag and camera to represent my spirit as a BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Colour) Queer filmmaker, my embodiment of Kali included a poignant moment in which I, dressed as the goddess, shared a cigarette with a street dweller at the park near Kensington Market. This moment, which was intended to highlight the radically inclusive nature of the deity whose image I grew up with, made its way onto the poster for the film, which I proudly shared on social media.

While I slept in my campus residence on the night of 2 July, Twitter India started trending with thousands of tweets, all with the same hashtag: #ArrestLeenaManimekalai. Literally overnight, a tsunami of death threats, rape threats, and other hateful abuse flooded my timelines, spewed from the keyboards of enraged Indian netizens who felt that my film poster had insulted Kali.

While I slept in my campus residence on the night of 2 July, Twitter India started trending with thousands of tweets, all with the same hashtag: #ArrestLeenaManimekalai. Literally overnight, a tsunami of death threats, rape threats, and other hateful abuse flooded my timelines, spewed from the keyboards of enraged Indian netizens who felt that my film poster had insulted Kali.

It took a moment for me to fully comprehend what was happening; like so many other Indian artists and activists in recent years, I had become the victim of Hindu fundamentalist cyber-vigilantes’ carefully orchestrated campaign of digitized violence.5 My poster, it seemed, had become the fodder for their hate machine.

The abuse was not just limited to me—my crew, family, friends, and even more distant acquaintances all were trampled by monstrous amounts of online hate and slander. This vicious hate campaign also extended into the real world—in addition to several police cases filed against me in various Indian states,6 a “lookout notice” that gives Indian police the power to ‘trace’ accused criminals abroad,7 as well as an open call to behead me by a Hindu religious leader—all for the “crime” of artistic expression.8

Fascism always demands loyalty to a single authority, often to a single race or religion. In my case, fascism came in the form of a statement by the Indian High Commission in Ottawa, demanding that Toronto Metropolitan University and the Aga Khan Museum withdraw my film.9 Instead of standing by their professed values of free speech and creative expression, these institutions gladly fed me to the wolves.10 First, they caved to the smear campaign by issuing statements of regret and distancing themselves from my film, a move which was praised by far-right Indian media and fuelled the relentless witch hunting against me. Several organizations such as Humanist’s International, Frontline Defenders, PEN Canada, Artists at Risk Connection, Dalit Solidarity Forum of USA, India Civil Watch International, Poetic Justice Foundation, Hindus for Human Rights, and XFA Equity Committee of TMU came together and mounted a protest screening to remind the University of its commitment to Academic Freedom.

On 20 January 2023, the Supreme Court of India heard my plea challenging the Union Government and granted interim relief protecting me from any coercive action by the Police and recorded that my Kaali film poster was not meant to insult religious feelings.11 Further on 10 April 2023, the Chief Justice of India extended the protection, transferred all the criminal cases to the Delhi High Court and directed me to approach to have the case quashed.12 The Delhi Police is yet to file a report under Section 173 of the Code of Criminal Procedure that could allow me to appeal to have the case quashed and I am learning that this delay is a menacing tactic in the cases of political persecution, as the State wants to keep the knife hanging over the heads of citizens who refuse to be silenced.

This may read as a story of trauma, but I see it as a story of a triumph. As an artist, my faith in the power of art is reiterated when a single image rattled the entire population of bigots, caste supremacists, hetero patriarchs, religious fundamentalists et al and rallied secular communities across the world to protest, cultivate solidarity, and push for systemic change.

Art can be many things to many. For me, art is resistance.

Foreword to the 2023 edition

By Panayote Dimitras

Panayote Dimitras is the co-founder of the Humanist Union of Greece

Thirty years ago I co-founded the Greek Helsinki Monitor and Minority Rights – Greece and in 2010 the Humanist Union of Greece, a Member of Humanists International. Inspired by humanist values, all three NGOs aim at promoting human rights and combatting all forms of discrimination, especially against minorities. In fact, it was the defense of the rights of ethnic minorities that had forced me out of the state university where I was teaching; in a violation of my academic freedom they first banned my book, because of the reference to minorities, and then denied me the right to attend international conferences.

Thirty years ago I co-founded the Greek Helsinki Monitor and Minority Rights – Greece and in 2010 the Humanist Union of Greece, a Member of Humanists International. Inspired by humanist values, all three NGOs aim at promoting human rights and combatting all forms of discrimination, especially against minorities. In fact, it was the defense of the rights of ethnic minorities that had forced me out of the state university where I was teaching; in a violation of my academic freedom they first banned my book, because of the reference to minorities, and then denied me the right to attend international conferences.

From the very first steps, I knew that my colleagues and I would face intense and quasi-continuous harassment from the authorities, as Greece has lacked a culture of human rights and in many aspects has been an illiberal democracy. In July 1993, along with activists from Human Rights Watch and the Danish Helsinki Committee we had a fact-finding mission to investigate the problems of the Macedonian minority, the existence of which all Greek governments have to this day refused to even acknowledge. A detailed report by the secret service including names and car licenses of all people interviewed by the mission was subsequently published by the most notorious extreme right neo-Nazi weekly “Stohos” on 15 September 1993. However, the three NGO reports published indelibly put the, until then, totally unknown, nationally and internationally, Macedonian minority on the map. A full fifteen years later, in 2008, I was criminally investigated for “attempting by force or by threat of force to detach from the Greek State territory belonging to it” because of our NGO work on the very same Macedonian minority, following a complaint by Greece’s most notorious neo-Nazi author and politician. It took a whole year before the file was archived. Six years later, in July 2015, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that Greece had for the second time violated the freedom of association of a Macedonian minority association, following an application submitted to the Court by Greek Helsinki Monitor.

Since 2015, Greek Helsinki Monitor has systematically reported or filed complaints in hundreds of cases of hate speech or hate crimes and, since 2021, of violent and sometimes fatal push-backs of asylum seekers. Although more than 150 of them led to trials or pressing of criminal charges, the rotating Prosecutor for Racist Crimes in 2020 charged me with filing false complaints, charges dropped at the end of 2021.

A year later in late 2022, a prosecutor on Kos island charged me with “forming or joining for profit and by profession a criminal organization with the purpose of facilitating the entry and stay of third country nationals into Greek territory” because I had reported to the local authorities the arrivals of asylum seekers on the island in July 2021; I did this to make sure that they would be registered and not pushed back, a common practice carried out in coordination with the UNHCR and the Greek Ombudsman. As a result of the charges, they imposed restrictive measures, such as a ban to work with GHM (lifted in May 2023) and to travel abroad, plus set a bail of 10,000 euros, required my fortnightly presence at the local police station, and, in May 2023, the freezing of one personal bank account! These measures are all designed to pressure me to stop my work to promote and defend human rights in Greece; a pattern of behavior on behalf of the Greek authorities that has been acknowledged by the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders and the Council of Europe’s Human Rights Commissioner.

I will however conclude with a positive development: following a series of Court judgments against Greece in 2010-2012, bearing the name Dimitras and others v. Greece, for violation of religious freedom when I and most GHM and Humanist Union of Greece colleagues had to state their non-religious/atheist beliefs in order not to take the mandatory religious oath in courts, the law was amended in 2012 to conform with the judgments and then again in 2019 to totally abolish religious oath in criminal proceedings. In a country notorious for the dominant role of the widely intolerant Orthodox Church, this was a notable success for my (our) humanist values, as was the 2015 extension of civil partnership to same-sex couples, in implementation of another ECtHR judgment after an application that I was privileged to have filed to the Court. Now, we are fighting for the right to be exempted from religious education without mentioning one’s religion in the request, which the authorities persist to refuse despite another ECtHR judgment against Greece.

Foreword to the 2022 edition

By Rishvin Ismath

Rishvin Ismath is the Founding President of the Council of Ex-Muslims of Sri Lanka

Experiencing freedom is something as rare as finding hen’s teeth to me. When I was a kid, my freedom was either stolen or controlled by elders such as parents, teachers, relatives, even the neighbors, or rather I did not know there was something called freedom. Being born in Jaffna, the capital of the northern peninsula of Sri Lanka, which was the hotbed of the civil war, I felt crippled as my movements were also controlled due to the war; I was only reminded that I had legs during those times when we all had to run and hide from flying bullets and blasting bombs. This was almost the same childhood biography for every child who grew up there.

As a teenager I was becoming an Islamist; I did not have the freedom to practice everything that I studied and believed to be the guidance of the so-called “almighty god” portrayed by my now ex-religion. I had to use a virtual padlock on my mouth not to talk about whatever I studied and believed, and the words of the so-called God, to save myself from trouble. I was very well aware that I would be arrested, if I practiced what my religion taught me. It’s possible that every Islamist would go through the same until they become a jihadist.

Once I opened my eyes wide and realized that I was fooled by imaginations, fictions, lies… utter lies, I left the religion, and yet I did not have the freedom to declare myself as an ex-Muslim, because I was conscious of the consequences.

When I did eventually declare my true self—an ex-Muslim—to the public, it was before the media at the Parliamentary Select Committee on 20 June 2019, while I was giving testimony regarding the Easter Sunday Suicide Attacks. After that, I lost the last iota of the freedom I had. There was an unannounced bounty on my head for leaving Islam. I happened to choose to live in the dark, in hiding. Over the years, there have been several unsuccessful attempts on my life, confirmed to me by the state intelligence of the country. I have been living in fear; I am forced to spend my days in hiding and running for safety. I live my life online.

Foreword to the 2021 edition

By Dr Ahmed Shaheed

Dr Ahmed Shaheed is the United Nation’s Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief

Rene Descartes found ‘thinking’ as proof of existence, a recognition that highlights the central role of the freedom of thought for every human being. Enshrined in Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the freedom of thought is a universal human right that protects everyone, everywhere, every single day. Safeguarding freedom of thought is not only imperative because it is a standalone right that demands absolute protection, but also because it is closely related to other fundamental rights, including the right to freedom of religion or belief, which covers theistic, non-theistic, atheistic and non-religious beliefs.

Rene Descartes found ‘thinking’ as proof of existence, a recognition that highlights the central role of the freedom of thought for every human being. Enshrined in Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the freedom of thought is a universal human right that protects everyone, everywhere, every single day. Safeguarding freedom of thought is not only imperative because it is a standalone right that demands absolute protection, but also because it is closely related to other fundamental rights, including the right to freedom of religion or belief, which covers theistic, non-theistic, atheistic and non-religious beliefs.

On 19 October 2021, I presented my report on “Freedom of Thought” to the UN General Assembly (UN Doc A/76/380) thereby aiming to provide practical guidance to rights-holders and duty-bearers alike on how to respect, protect and promote this fundamental if unexplored right. In that report, I observe that

freedom of thought is not only foundational for enjoying freedom within religion or belief (i.e. in choosing, exercising and converting one’s religion or belief), but also for exercising freedom from religion in thinking freely on all matters without the influence of religion or belief systems. In this regard, both religious and non-religious may cherish freedom of thought as a vehicle for reason, the search for truth, and individual agency.

In consultations conducted and submissions received for the report, I also heard from diverse stakeholders including several members of the Humanist community worldwide about the importance of “free-thinking,” encompassing the need for critical thinking skills through education, and how State and non-State actors may violate the right to freedom of thought. Specifically, I received a number of reports that anti-apostasy and anti-blasphemy laws could infringe upon freedom of thought of vulnerable individuals and groups, including atheists and dissenters from religion. Such laws criminalize and censor free expression of one’s thoughts out of fear of reprisals and restrict access and circulation of materials, including free and open Internet access, which could facilitate critical thinking.

A fundamental point to remember always is that freedom of religion or belief, as a human right, protects human beings, not religions or beliefs, as such. I have repeatedly called on States to repeal anti-blasphemy and anti-apostasy laws since they undermine both freedom of religion or belief and the ability to have healthy dialogue and debates on a wide range of human concerns, including religion or belief. I am deeply concerned that several States have maintained these oppressive laws and even impose the death penalty for those found in breach. Far from promoting public order, as many states that use these laws claim, these laws inhibit social capital and undermine the rule of law and frequently empower vigilante attacks.

Humanists International and other civil society organisations play an invaluable role in documenting human rights violations, holding the powerful to account for their violations of freedom of thought and freedom of religion or belief. I welcome the publication of the 2021 Freedom of Thought Report of Humanists International, in recording the experiences of not just humanists and the non-religious all over the world, but also those who may be deeply religious but are dissenters, illuminating both key trends and individual cases of concern. Targeting individuals with hatred, violence and discrimination based on their religion or belief identity is contrary to international human rights law, and has no place in any society.

The annual report is not only a useful monitor of developments worldwide, but also a valuable resource to those who champion freedom of thought, conscience and religion or belief for all. Issued on the eve of the 40th anniversary of the UN Declaration on the Elimination of all Forms of Intolerance and of Discrimination Based on Religion or Belief (UN Doc A/RES/36/55), the present report is also a timely and compelling call to action.

Foreword to the 2020 edition

By Mohamed Cheikh Ould Mkhaitir

Everything seemed to be normal in that land that had been dating the sea since eternity, the two gave birth to a city and agreed to call it: “Nouadhibou”. And it was a female city …

Everything seemed to be normal in that land that had been dating the sea since eternity, the two gave birth to a city and agreed to call it: “Nouadhibou”. And it was a female city …

And everything seemed normal… until I wrote my article about slavery and social injustice and their relationship to religion, from then on everything turned upside down:

- I was placed in an isolation cell

- I was denied the right to family visits

- My wife was divorced from me and forcibly married to another man

- Nothing was normal anymore …

Raging waves of bloodthirsty extremists filled the streets and their only demand was my head.

Why all this fuss? It was simply an article I wrote in which I demanded that slavery and racial discrimination should be abolished. I knew that I had touched a nerve when I showed from the old and recent Islamic history and theology that slavery and the caste system in Mauritania and -other Muslim countries- are practices primarily stemming from and legitimated by religion and do not resemble most of other types of slavery that existed in other parts of the world, such as the United States, which had an economic character.

Because the article called also for freedom of religion or belief, and it was written by a person descended from the “maalemine” caste [translator’s note: darker-skinned people descended from blacksmiths, carpenters and other skilled laborers regarded as “low caste” and still subject to discrimination], this was for the masters an indication that the time of silence had gone with the wind.

Because I said “no to slavery and caste discrimination” I had to spend six years of my life behind bars, six years in solitary confinement. After a year in imprisonment I was sentenced to death, which was upheld by the Court of Appeal two years later. The accusation was “apostasy,” and the evidence against me was words I wrote in the aforementioned article and other articles where I called for freedom of religion or belief and individual liberties for all.

I do not regret any of the minutes, weeks and years I spent in the corridor of death, because every change has a price, and what would you say, if the change we aspire for, would take us from darkness to enlightenment, from slavery to liberty…? It is indeed a price worth fighting for.

A large part of what I have experienced is the responsibility of some influential human rights organizations and the so-called leaders of the free world, many of these organizations do not care about the misery that the people of Mauritania have to endure. There are several reasons for this, the most important of which is the lack of the economic and geostrategic significance of Mauritania. It’s the “curse of geography” as my friend Kacem El Ghazzali calls it.

In this context I must mention – and it is something I will never forget as long as I live – the role played by “International Humanists” in advocating my freedom and supporting me and my family. I will never forget the repeated phone calls of Kacem El Ghazzali to my family in the early days of my imprisonment, Kacem El Ghazzali, Elizabeth O’Casey, Bob Churchill, Gary McLelland and all their comrades at Humanists International who were in fact my voice, my direct voice from the death cell in Mauritania to the entire world, including the UN Human Rights Council.

Having the honor to write this forward of the Freedom of Thought Report, I would like also to call for :

Granting freedom of religion or belief, and abolishing blasphemy laws all over the world, especially in Islamic countries.

Strengthening the role and rights of women in society and eliminating the shameful discrimination that they are exposed to.

Combating slavery, which is a disgrace to our societies in the twenty-first century.

Eliminating all kind of discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation.

I also call on international Human Rights groups to be fair, and that their interests should not be based on the economic geopolitical interests. It is a shame for humanity that the human rights situations in North Korea, Iran, Saudi Arabia and China consistently take the spotlight, while there is little to no mention of the severe human rights violations taking place in the Sahel region

I must also mention our Humanist friends in Nigeria who are being imprisoned on charges of apostasy and blasphemy, and I ask for their immediate release.

Thank you Humanists International and all the best with your very much needed work!

Translation by Kacem El Ghazzali

Foreword to the 2019 edition

By Mohamed Hisham Nofal

I am Mohamed, a human rights and LGBT rights activist. I am also an electrical engineer by profession. Currently, I live in Germany after escaping my home country Egypt for practising my fundamental right of freedom of speech.

I am Mohamed, a human rights and LGBT rights activist. I am also an electrical engineer by profession. Currently, I live in Germany after escaping my home country Egypt for practising my fundamental right of freedom of speech.

Back in Cairo, February 2018, I confronted a government Imam live on TV. I had been invited on to talk about why I professed atheism. I was very polite. I explained why in my opinion religion was not logical. Before I could conclude, I was told I needed psychiatric help and thrown off the show.

As a consequence, my life took a dramatic turn. Living safely in my country became inconceivable. I received death threats. The police searched my house. I had taken the decision to go public with my convictions while I was totally willing to endure the consequences of challenging religion in such a public setting. Because for me a life where my basic personal freedoms are illegal and can’t be practised is not worth living.

In my part of the world, there are too many destructive beliefs and ideas that are held by both the public and the government as sacred or untouchable. But in order for the MENA region to progress towards being a peaceful region that respects human rights and contributes more positively to human civilisation, many mainstream “sacred” and “holy” ideas and beliefs will have to be challenged and changed.

This can’t happen in such oppressive environments as the one we have in Egypt for instance. Our government’s crackdown on freedom of speech is happening because they installed an authoritarian, fragile system that would allow the country to be driven easily to complete disorder and chaos if they ceased to use force to oppress the people. So, we urgently need new humanistic governing systems that would give us enough freedom to allow us to pursue these needed changes.

Many people are trying to change the status quo in my country, but sadly I am considered lucky in comparison to friends who ended up in prison or got stuck in inhuman and dangerous situations. I wish them freedom and safety.

The international community must unite around the ideals of peace and human rights, do not give up on countries like mine, do not pretend that the politics is too hard or that no form of intervention is possible or desirable. There is always something you can do toward building up human rights. Use your imaginations. Develop new strategies. Promote the human rights we need however you can. I beg you to do it.

Foreword to the 2018 edition

By Ahmedur Rashid Chowdhury

Ahmedur Rashid Chowdhury is a writer, publisher and activist from Bangladesh, now living in Norway

In my home country of Bangladesh, I was a publisher. I published books on science, philosophy, and politics. I encouraged young writers to read different perspectives on issues, to be informed, and to think for themselves. I believe that a healthy society is one in which all people are encouraged to read, think, discuss, debate, and learn from each other. It is only with creativity and a diversity of ideas that we will be able to address the challenges of this era.

In my home country of Bangladesh, I was a publisher. I published books on science, philosophy, and politics. I encouraged young writers to read different perspectives on issues, to be informed, and to think for themselves. I believe that a healthy society is one in which all people are encouraged to read, think, discuss, debate, and learn from each other. It is only with creativity and a diversity of ideas that we will be able to address the challenges of this era.

In 2015, radical Islamists tried to stop me. You came into my workplace with machetes and a gun. I was very fortunate to survive your attack. That same year, you had already killed my friends, bloggers, and authors. That same day, you killed my fellow publisher Faisal Arefin Dipon. Even this year, you killed another publisher, Shahzahan Bachchu.

What have you achieved with all this death? You create terror, but terror does not make your beliefs any truer.

To the government of Bangladesh, this is my message: freedom of expression – a cornerstone to democracy – is under serious threat from radical Islamists, governmental policies, and inaction by authorities to uphold justice. Through your actions, you support and protect Islamic terrorists who kill and silence members of our community. You do not arrest and bring to justice the killers of writers and publishers. You use Section 57 of Bangladesh’s Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Act to censor online speech and to crack down on artists, writers, and activists. Instead of creating a safe environment for constructive civic debate and democratic participation, you intimidate and silence voices of dissent in Bangladesh. I beseech you to remember that Bangladesh is home to creative, energetic, and inspiring individuals who love this nation, its history, and its culture. It is only through a healthy democratic environment where freedom of speech is fostered that we will be a strong nation. Fear will not lead to this future.

To the fundamentalists, this is my message: when it comes to theory and debate, you can say or write anything you like, just as I can say or write anything I like. But when you motivate others to kill, when you radicalize them to terrible acts because you do not like to hear the words of others, this is not an act of strength, but of weakness. It shows a weakness in heart and mind, and it reveals the weakness of your own arguments or beliefs. If you believe in the value of your words and in the truth of your beliefs, then you have no reason to fear others who express different words and beliefs. More importantly, silencing people through death and terror sets back the development of all of society for everyone.

In my adopted country, far from home, I am still a publisher. I will debate with anyone. I will write. I will give my answers. Even here in exile, I write and I publish. I write against your censorship. I write to promote freedom of expression and democratic values of respect. I write against your terror and in favour of humanism and reason. Your fear, your hatred, and your terror never made a single thing you believe truer, never made a single thing I believe less true.

Words cannot be killed.

Foreword to the 2017 edition

By Ensaf Haidar

Ensaf Haidar is a human rights activist, campaigner for the release of her husband, Raif Badawi, and other prisoners of conscience in Saudi Arabia

In 2012, my husband, Raif Badawi, was arrested in Saudi Arabia. He had helped to set up a liberal blogging platform. In his own blog, and in opinion pieces for newspapers, he expressed his opinion: that the clerics should have less to do with the business of the state, because an excess of religious conservativism was damaging to society. Today, this opinion becomes ever more common, even among royal reformists!

In 2012, my husband, Raif Badawi, was arrested in Saudi Arabia. He had helped to set up a liberal blogging platform. In his own blog, and in opinion pieces for newspapers, he expressed his opinion: that the clerics should have less to do with the business of the state, because an excess of religious conservativism was damaging to society. Today, this opinion becomes ever more common, even among royal reformists!

But just for expressing his opinion, Raif faced the possibility of a death sentence on “apostasy” charges, and was eventually sentenced for “insulting Islam” to a long prison term and lashes. On appeal, his sentence was increased to ten years prison and 1,000 lashes. He also faces a ten-year travel ban after his sentence.

Raif has the terrible and unwanted honour now of being probably one of the most famous prisoners in the world. But many bloggers, journalists and activists in too many countries face similar charges and punishments. There are many issues at play in such prosecutions. Authoritarian regimes suppress opinions which they think are a threat to their own power.

Humanist and human rights groups internationally have repeatedly called for the release of Raif Badawi. Here, Norwegian Humanists and Amnesty protest at the Saudi Arabian embassy in Oslo, Friday 16 January 2015

However, in the context of this Freedom of Thought Report, I want to highlight the role that is played when the authorities evoke religion to suppress these ‘troubling’ opinions.

Raif wrote about politics and society. Yet just because some of his opinions overlap with religion or offer criticisms of religious authorities he can be imprisoned for “insulting Islam”.

Raif describes himself as a liberal Muslim, and yet his country tried him for “apostasy”. The idea that he might have left Islam was used to demonize him. It does not matter if you are a humanist or a Muslim, an atheist or a Jew, an agnostic or a Christian. No one anywhere should face such trial just for expressing their view of the world. Freedom of thought and expression are our human rights.

I reject the idea that anyone, or any state, has the right to threaten someone with death just because they believe or don’t believe in any religion. I reject the idea that just because someone thinks critically about any aspect of religion they deserve to be prosecuted, still less to be imprisoned, separated from their children for years and years and years.

It is in everyone’s interest (religious, non-religious, anyone) that we shine a powerful light on the spectre of atheism. Shine a light, and the shadow will lift! And we will find that there is no spectre. Only a human being.

Foreword to the 2016 edition

By Ahmed Shaheed

Dr Shaheed is the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief, as of 1 November 2016.

The right to freedom of religion or belief is a right that is frequently misunderstood by its conflation with narrowly defined views on religious freedom.

The right to freedom of religion or belief is a right that is frequently misunderstood by its conflation with narrowly defined views on religious freedom.

Such narratives often overlook the fact that the freedom of religion or belief includes the freedom of thought and conscience, protected on an equal footing under international human rights law. Moreover, as the Human Rights Committee points out, “religion” and “belief” are to be understood broadly, covering theistic, non-theistic, and atheistic beliefs. Thus, the freedom of religion or belief protects individuals who adhere to traditional as well as new religions and to majority or minority faith communities, and those who are dissenters or who subscribe to no religion or belief at all or who are unconcerned. In fact, international human rights law protects both the freedom of religion and its corollary, the freedom from religion, for without the latter, the former has no practical meaning at all.

As I write these words at the end of 2016, I am deeply distressed by the rising intolerance related to religion or belief worldwide. Global trends clearly show a resurgence of religiously motivated action in the public square. While this phenomenon in and of itself, should not be a problem, it can become a challenge where it is accompanied by claims of religious privilege—contrary to the limits set by Article 5.1 (or indeed Article 18.3) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. On the one hand, there are the atrocious violations of religious freedom rights in situations of intra-state conflict as in the case of the monstrous crimes committed by the Daesh in Syria and Iraq; the brutal attacks on the Rohingya in Myanmar; or the heinous activities of the Boko Haram in Nigeria. On the other hand, established democracies are also reporting rising levels of intolerance including anti-Semitism and anti-Muslim sentiment. The outrage over the former and the shock over the latter often distract from the horror of the persistent violations of the human right to freedom of religion or belief in the numerous countries that suppress religious freedom either through blasphemy and apostasy laws or through other claims of privilege based on religion or belief.

Nearly 70 years after the proclamation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights that protects the right to freedom of religion and freedom from religion for all, blasphemy is outlawed in at least 59 countries punishable with a prison term or in some cases death. At least 36 countries continue to enforce their anti-blasphemy laws. There are laws against apostasy in 22 countries, and at least 13 countries provide for the use of the death penalty for blasphemy or apostasy. While anyone can run afoul of these laws, and often there are allegations of the use of such laws for political purposes, these laws potentially automatically criminalize dissent and free-thinking, and victimize “non-believers”, humanists and atheists. What is even more shocking is the cruelty with which those who are accused of violating these laws are often punished– by state agents or by non-state actors, including neighbours and relatives.

I therefore welcome the publication of the 2016 Report of the International Humanist and Ethical Union, documenting the situation of atheists, humanists and free-thinkers all over the world. From Raif Badawi, who was sentenced to 1000 lashes and 10 years in prison in Saudi Arabia for alleged “blasphemy”; to Mohamed Cheikh Ould M’kheitir, who is facing the death penalty and incitement to murder in Mauritania for alleged “apostasy”; to Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, the mayor of Jakarta who is accused of “blasphemy” amidst an election; to those secular bloggers savagely hacked to death in Bangladesh by vigilante groups; to the scores languishing in prison in Pakistan and Iran and elsewhere for expressing views deemed offensive to religious sentiment; persecution and victimization in the name of religion are both chilling and widespread.

The IHEU report is an important reminder that the right to freedom from religion or belief is as fundamental as the right to freedom of religion, and that the same human right protects freedom of non-religious thought and non-religious belief as well; and that for some humanists, atheists, free-thinkers and the unconcerned the protection of this right can mean the difference between life and death. The report also underscores the principle that the rights and protections in the human rights framework should not, and cannot, be exercised in such a way as to destroy other fundamental rights articulated in the Universal Declaration, such as the right to life, the right to equal treatment before the law, the right to freedom of opinion and expression, and indeed the right to freedom of religion or belief itself. The documentation of rights violations is a crucial step in mobilizing actors against continued or further violations. It is my hope that this publication will not only shed light on existing practices that must change to conform to international human rights law, but will also serve as a vigil to those who have been targeted by blasphemy and apostasy laws or otherwise been victims of religious intolerance the world over.

Extracts from earlier forewords

The first report was published in 2012 on International Human Rights Day, 10 December. In his preface to the report, the United Nations Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Religion or Belief, Professor Heiner Bielefeldt (in post 2010-2016), said:

“As a universal human right, freedom of religion or belief has a broad application. However, there seems to be little awareness that this right also provides a normative frame of reference for atheists, humanists and freethinkers and their convictions, practices and organizations. I am therefore delighted that for the first time the Humanist community has produced a global report on discrimination against atheists. I hope it will be given careful consideration by everyone concerned with freedom of religion or belief.”

For the 2013 report we asked two victims of anti-atheist persecution to provide the introductory remarks. The cases of Kacem El Ghazzali and Alber Saber, from Morocco and Egypt respectively, also feature in the report. They said:

“In spite of international treaties and conventions, many states discriminate in subtler but important ways. And this has a global impact. Laws against “insulting” religion in relatively secure, relatively secular countries, for example, are not only analogues of the most vicious blasphemy laws anywhere in the world, but help to sustain the global norm under which thought is policed and punished.

We welcome this report. The world cannot fix these problems until they are laid bare.”

In 2014, in their preface, Gulalai Ismail and Agnes Ojera, both working to promote human rights in Pakistan and Uganda respectively, said:

“The rights of the non-religious, and the rights of religious minorities and non-conformists, are a touchstone for the freedoms of thought and expression at large. Discrimination and persecution against the non-religious in particular is very often bound up with political suppression, with fears about progressive values, or with oppression in the name of religion. Humanists and secularists are often among the first to ask questions, and to raise the alarm when human rights are being trampled, when religion is misused or abused, or — even with the best intentions — if religion has become part of the problem. Silence the non-religious, and you silence some of the leading voices of responsible concern in society.”

In 2015, following a series of gruesome murders of non-religious writers, bloggers and human rights activists in Bangladesh, targeted by Islamist militant groups for “insulting Islam”, Rafida Bonya Ahmed, whose husband was the first to be killed in this way that year, said:

“If there are lessons the world must draw from Bangladesh in recent years, they are these: Allowing bigotry and extremism to fester unchallenged will have generational consequences; Demands for prison or death sentences or vigilantism against humanists as such must be met not with appeasement nor by arresting the very bloggers under threat, but with condemnation as the gross violations of freedom of thought and expression that such demands represent; And that once a country silences and intimidates its intellectuals and freethinkers , a vicious cycle of terror and extremism becomes inevitable…”

- “Landing page”, iamstory.org, accessed 4 November 2024, https://iamstory.org/#Landing_page [↩]

- “Under the Tent launch,” Toronto Metropolitan University, accessed 4 November 2024, https://www.torontomu.ca/cerc-migration/events/2022/07/under-the-tent-launch/ [↩]

- Note: Takaronto is considered the original name of the city of Toronto. For more information see: Misha Gajewski, “This is why more people are now referring to Toronto as Tkaranto,” BlogTO, 8 August 2020, https://www.blogto.com/city/2020/08/why-toronto-tkaronto/ [↩]

- Sumanta Banerjee, “Revisiting Kali: An Amalgam of Aboriginal Deities and a Symbol of Rebellion,” The Wire, 19 July 2022, https://thewire.in/religion/kali-aboriginal-roots-and-symbol-of-rebellion [↩]

- Nazneen Mohsina, “Hindutva Vigilantism: Online Hate, Offline Harms,” Global Network on Extremism & Technology, 22 October 2020, https://gnet-research.org/2020/10/22/hindutva-vigilantism-online-hate-offline-harms/ [↩]

- “FIRs in Delhi, UP Against Leena Manimekalai for ‘Kaali’ Documentary Film Poster”, The Wire, 5 July 2022, https://thewire.in/film/fir-against-filmmaer-leena-manimekalai-for-kaali-documentary-film-poster [↩]

- “Madhya Pradesh Police Issue Lookout Circular Against Leena Manimekalai”, Outlook India, 8 July 2022, https://www.outlookindia.com/art-entertainment/madhya-pradesh-police-issue-lookout-circular-against-leena-manimekalai-news-207667 [↩]

- PTI, “Ayodhya Priest Threatens to Behead Filmmaker Leena Manimekalai”, The Wire, 6 July 2022, https://thewire.in/film/ayodhya-priest-threatens-to-behead-filmmaker-leena-manimekalai [↩]

- “‘Kaali’ film row: Indian High Commission asks Canadian authorities to remove ‘provocative material’”, Indian Express, 5 July 2022, https://indianexpress.com/article/india/kaali-film-row-indian-high-commission-canada-to-remove-provocative-material-8009735/ [↩]

- “Statement on Freedom of Speech”, Ryerson University Senate, 4 May 2010, https://www.torontomu.ca/content/dam/senate/documents/Statement_on_Freedom_of_Speech_May_04_2010.pdf; “About the Aga Khan Museum”, Aga Khan Museum, https://agakhanmuseum.org/about/ (accessed 4 November 2024)[↩]

- Lisa Xing, “India’s Supreme Court grants protection to filmmaker attacked for movie poster featuring Hindu goddess”, CBC, 22 February 2023, https://www.cbc.ca/news/entertainment/kaali-goddess-leena-manimekalai-court-order-1.6755493 [↩]

- Debayan Roy, “Kaali poster row: Supreme Court directs transfer of all FIRs against Leena Manimekalai to Delhi Police”, Bar & Bench, 10 April 2023, https://www.barandbench.com/news/litigation/kaali-poster-supreme-court-transfer-firs-leena-manimekalai-delhi-police [↩]