Georgia

Table of Contents

A former Soviet republic which declared its independence in 1991, Georgia is today a semi-presidential republic, lying at the intersection of Europe and Asia. While Georgia experienced a period of democratization from 2013 until 2017, observers consider that Georgia has experienced significant democratic and human rights backsliding since 2023.1 The V-Dem Institute downgraded Georgia from an “electoral democracy” to an “electoral autocracy” in 2025, noting that the 2024 election year “marked the largest one-year decline since Georgia’s independence.”2

The northern regions of South Ossetia and Abkhazia declared independence from Georgia in the 1990s – though there is little international recognition for their independence – and Georgia considers them part of its sovereign territory. Following the Russo-Georgian War in August 2008, both territories have been under Russian occupation. In 2021, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) ruled that Russia has effective control of the territories and can be held responsible for human rights violations in the two regions.3

In November 2024, Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze announced that Georgia would suspend its European Union (EU) accession efforts until 2028, after the EU halted the process as a result of the country moving “away from the European Union, away from its values and principles.”4

According to the most recently published census in 2014, 83.4% of Georgians identified as Christian Orthodox, followed by Muslims at 10.7%.5 Only 1.73% did not provide an answer, or responded “none,” when asked whether they were religious.

| Constitution and government | Education and children’s rights | Family, community, society, religious courts and tribunals | Freedom of expression advocacy of humanist values |

|---|---|---|---|

Constitution and government

Article 16 of the Constitution of Georgia6 guarantees freedom of belief, religion and conscience for all. In 2017, the Parliament of Georgia drafted amendments to the Constitution that would allow restrictions to Article 16 under ambiguous terms including “state security,” “prevention of crime,” and “administering justice.” The proposed changes were heavily criticized by the Council of Europe’s Venice Commission and civil society.7 After being initially adopted, the parliament amended Article 16 in 2018 to allow restrictions only “for ensuring public safety, or for protecting health or the rights of others, insofar as is necessary in a democratic society.”8

The Constitution and government policy confer special status and privileges to the Georgian Orthodox Church (GOC). Article 8 recognizes the GOC’s “outstanding role […] in the history of Georgia” and its independence from the State, but also allows for a “constitutional agreement” (known as the “Concordat”) to be signed between the State and the Church.9 The Concordat was signed in 2002 and confers a unique status upon the GOC; the government does not have a similar agreement with any other religious group. It confers rights not given to other religious groups, including legal immunity for the GOC patriarch, the exclusive right to staff the military chaplaincy, and exemption of GOC clergy from military service.10 Clergy from other religious groups are not granted such privileges and must perform a non-military, alternative labor service. The Concordat recognises GOC wedding ceremonies. However, a marriage is only legally recognised after civil registration with the State. Additionally, the Concordat provides special privileges in the area of education (including the GOC’s right to teach religious studies in public schools and the State’s authority to pay for Georgian Orthodox religious schools) but these education provisions have not yet been implemented.11

Other religious communities may register with the National Agency of the Public Registry as a legal entity under public law or as a non-commercial entity, both of which grant legal recognition, tax exemptions, and the right to own property and operate a bank account.12 Non-registered communities can still conduct religious activities and own property. While legal entities under public law must have a historic link with the country or be recognized as a religion by Council of Europe member states, this requirement does not apply to non-commercial entities. The governmental body dedicated to engagement with religious communities, the State Agency for Religious Issues, has been criticized by civil society for seemingly being focused on the monitoring and control of religious minorities.13 The Agency’s Interreligious Council includes 12 religious organizations but no humanist or other non-religious worldview organizations.

Financially, the Concordat and other legislation grant the GOC compensation for material and moral damages inflicted during Soviet times and exempt the Church from several taxes applicable to other religious groups, including property tax on land used for non-commercial purposes and taxes on the import or sale of religious goods.14 In 2018, an existing tax exemption for the construction, restoration, or maintenance of churches and cathedrals by the GOC Patriarchate was declared unconstitutional. However, a new provision introduced in 2020, mentioning “cathedrals” and “church buildings,” retains Christian terminology and remains religiously non-neutral. As in previous years, the GOC Patriarchate received GEL 25 million (approx. USD 9.3 million) in 2024 from the national government as symbolic compensation, as well as another GEL 39,364,180 (approx. USD 14.5 million) for various institutions under the authority of the GOC and a large amount of real estate. Typically, the Church receives another GEL 5–7 million (approx. USD 1.9–2.6 million) from local governments. Since 2014, four other religious organizations (Muslim, Jewish, Catholic, and Armenian Apostolic) have received state funding as symbolic compensation as well, totalling GEL 6.5 million (approx. USD 2.4 million) in 2024.15 Furthermore, the GOC is the only religious organization that may receive state property free of charge or directly purchase it, and it is granted ownership over state forests near GOC churches and monasteries.16

Georgia does not include religious affiliation in identity documents,17 and contributions to religious groups are voluntary and not state-administered.

Education and children’s rights

Georgia’s Law on General Education18 upholds the principle of religious neutrality in public schools, abolishing compulsory religious courses, banning religious indoctrination and proselytization, removing religious objects from schools, and allowing religious rituals to take place only after school hours.19However, according to various local and international reports, the law is frequently violated or circumvented.20 In 2022, the UN Human Rights Committee raised concerns about “allegations of stigmatization, pressure to convert, and harassment against members of religious minorities” in public schools.21

According to civil society reporting, the national curriculum and textbooks often reflect a majoritarian and exclusionary vision of Georgian society. For instance, school textbooks are said to fail to represent Georgia’s ethnic, cultural, and religious diversity and to negatively stereotype beliefs and ethnicities perceived as non-Georgian.22 The 2024 “Document of National Goals of General Education” removed liberal values and terms such as “discrimination”, which were present in the 2004 version. Also in 2024, a textbook approval process that involved human rights experts reviewing content for non-discrimination, was stopped by the Ministry of Education.23

About 11% of pupils attend private schools as of 2025.24 Roughly a quarter of all private schools are Orthodox schools, which are under control of the GOC Patriarchate. In 2025, the government allocated GEL 43 million (approx. USD 15.5 million) to fund these educational institutions, which are usually free or charge nominal fees.25 Other private schools do not receive state funding.

Serious concern has been raised in recent years about the abuse and mistreatment of children in the Ninotsminda St Nino Children’s Boarding School, an orphanage which is run by the Georgian Orthodox Church. Several children came forward with allegations of physical and psychological abuse, including insults, food and sleep deprivation for several days, confinement, and corporal punishment. Even after the Public Defender (ombudsperson) raised concerns about the school in a 2015 report, and repeatedly afterwards, the orphanage continued to operate legally and the authorities failed to investigate. After a visit in 2016, the Public Defender was denied her right to access the institution, with the bishop responsible for the institution stating that people who approve of same-sex marriages “should not be allowed into orphanages or any family in general.”26 It was only when judicial and administrative authorities started to intervene in 2021, that the Public Defender was eventually able to conduct a visit.27

The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child issued a decision in 2024 that Georgian authorities failed to effectively investigate and address the child abuse, and a case is pending in front of the European Court of Human Rights.28 The Committee is also more broadly concerned about the “significant number of children residing in non-licensed residential care institutions, including religious ones, and the lack of monitoring of the conditions in such institutions.”29

Although Georgia set the minimum legal age of marriage at 18 years old with no exceptions in 2017, child and forced marriages persist – especially in rural areas. Girls, in particular, can be subject to informal or “cultural” marriages, which are meant to circumvent the prohibition.30 Child marriage rates are said to be one of the highest in Eastern Europe with 13.9% of women aged 20–24 married before 18, according to one study.31 The UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women also raised concern about the fact that not all child marriages are considered forced marriages under Georgian law.32

Family, community, society, religious courts and tribunals

The Georgian Orthodox Church remains one of the most trusted institutions in the country. For a long time, being an Orthodox believer was considered an essential part of being a “true” Georgian (next to being ethnically Georgian and speaking the language). However, a 2020 survey found that such an ethno-religious definition of identity is no longer predominant. Only 50% of respondents agreed that Georgian citizens should be Orthodox Christians while only 29% agreed that they should be ethnic Georgians.33 However, the same survey found that 79% of respondents still view the GOC as the foundation of Georgian identity, and 80% see it as promoting the preservation of moral values.

Social prejudice against the non-religious

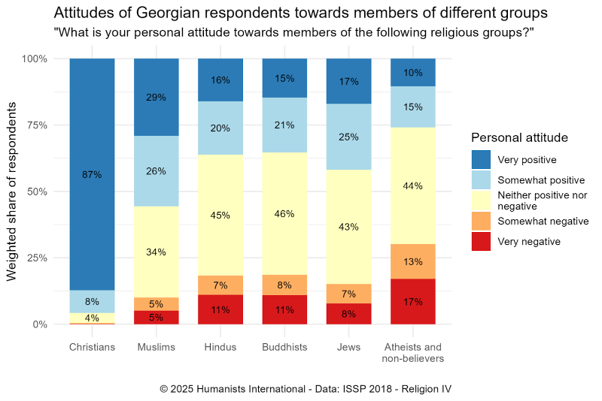

According to the latest data from the International Social Survey Programme, which Humanists International has conducted an analysis of in the figure below, negative attitudes towards the non-religious in Georgia are higher than towards any religious group. 30% of respondents have a “very” or “somewhat” negative attitude towards atheists and non-believers, compared with 15% for Jews and 10% for Muslims.34 Only 10% of respondents have a very positive attitude towards atheists.

Non-religiousness is often portrayed as immoral and anti-GOC, as well as negatively associated with the West and liberal values. Around the 2024 parliamentary elections, the Georgian Dream-led government rallied against human rights, civil society, and the West in the name of protecting the GOC, traditions, and “family values.” Human rights defenders, critical media, civil society, and opposition politicians were smeared as “blasphemers,” “enemies of the Church,” and “fighting against Christian values.” For instance, Georgian Parliament speaker Shalva Papuashvili stated that the election is a “choice between evil and good, ungodliness and spirituality.”35 At the same time, Orthodox clergy spread similar anti-West, anti-human rights messages about the opposition and civil society. They also linked the Georgian Dream governing party to the protection of the Church and preservation of Christian values and traditions. A central theme of that messaging by the clergy was its opposition to “Western” “LGBT propaganda.”36

LGBTI+ rights

Georgia has seen a cascade of legislative changes in recent years that undermines the rights of LGBTI+ persons, paired with the rise of political homophobia and high levels of societal discrimination and hostility. The GOC, the Georgian Dream governing party, and various far-right movements are the key actors driving this backsliding.

In particular, the 2024 Law on the Protection of Family Values and Protection of Minors imposes discriminatory restrictions on LGBTI+ persons and threatens their human rights. It introduces a prohibition for same-sex marriages or civil unions, following up on the 2018 amendments to the Constitution that explicitly define marriage as a “union between a man and a woman.”37 Community members are banned from adopting or fostering children. It also includes broad prohibitions on “promoting” LGBTI+ issues at public assemblies and educational institutions, in literature, film, and media, and even in direct communication with children.38 Additionally, the law bans legal gender recognition and criminalizes gender-affirming healthcare for transgender people. This contravenes a recent European Court of Human Rights judgment that held that Georgia establish mechanisms for legal gender recognition of transgender persons.39 There are also vague provisions that seek to strip transgender employees from any anti-discrimination protections regarding gender recognition in their employment, including those imposed by private agreements. The law also helps fuel anti-LGBTI+ narratives by perpetuating harmful stereotypes by alluding to a threat posed to children by LGBTI+ people and by conflating consensual same-sex relationship with incest.40 The day after the law was adopted, celebrity transgender woman Kesaria Abramidze was found brutally murdered in her home.41

Previously, the adoption of the Law on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination42 in 2014 signaled important progress in fighting discrimination as it explicitly included sexual orientation and gender identity as protected grounds. However, the lack of political will to prioritize LGBTI+ equality resulted in the law never being fully implemented or consistently enforced. Mentions of gender and LGBTI+ issues had already started disappearing from policy documents before the 2024 law, and the word “gender” was removed from all existing legislation in 2025.43Gender identity was also removed as a protected ground from the 2014 anti-discrimination law, leaving only sexual orientation.44 Legislative changes affecting civil society, including the Law on Transparency of Foreign Influence45 and the Foreign Agents Registration Act46 discussed below, have also significantly weakened LGBTI+ community organizing.47

On the rare occasions that LGBTI+ groups have attempted to hold peaceful public assemblies, they have been met with violence and harassment by counter protesters. Reports suggest that these counter protesters often belong to radical Orthodox Christian groups and have been incited by statements from GOC clergy.48 On 8 July 2023, thousands of far-right demonstrators, including clergy, stormed the site of the Tbilisi Pride Festival. It followed public threats against the event and calls by the GOC Patriarchate to ban so-called “LGBTQI+ propaganda.”49 After GOC and governmental leaders called for the Tbilisi Pride march to be cancelled in July 2021, radical conservative groups attacked the offices of Tbilisi Pride and the Shame Movement. They also violently assaulted journalists, activists, and human rights defenders.50 The de-facto second-in-command in the GOC, Metropolitan Shio Mujiri, labelled Tbilisi Pride “part of a large campaign which aims to distance the nation from God, our traditions, church and degrade it.”51 The Council of Europe’s European Commission against Racism and Intolerance raised concerns about GOC clergy comments surrounding the 2021 Tbilisi Pride, believing that they could be seen “as an incitement to violence against participants of the Pride events.”52 In 2012 and 2013, at peaceful assemblies during the International Day Against Homophobia, Transphobia, and Biphobia (IDAHOTB), LGBTI+ people were violently attacked by religious counter-demonstrators, including several Orthodox priests. To this day, there has been no effective investigation into the events of 2012, 2013, 2021, and 2023, and the perpetrators of the violence have not been held accountable. Amnesty International has asserted that the absence of justice reinforces “a dangerous trend of impunity in the name of religion.”53

These incidents are emblematic of wider political and societal hostility towards the LGBTI+ community. Ultranationalist and far-right groups harass and assault LGBTI+ people, while political and religious leaders spread anti-LGBTI messages, contributing to a rise in political homophobia.54 For instance, de-facto leader of the Georgian Dream party, Bidzina Ivanishvili, framed “LGBT propaganda” as a threat to the nation’s survival in 2024: “anti-Christian forces are trying to erase the identity of nations, states, and people. Their goal is to turn a person into a being devoid of dignity and morality, who will not have any national, religious, or personal identity; one should not even know for sure whether one is a man or a woman.”

As one of the most trusted institutions in Georgia, the GOC’s stance on LGBTI+ issues significantly shapes public opinion and fuels ultra-right movements that, in collaboration with GOC officials, frame LGBTI+ equality as a threat to Georgian identity, culture, and national values. These attitudes are reflected in wider society: A 2020 UN Development Programme study found that over half of women and 8 in 10 men would never have a homosexual friend, and even more would be ashamed if they had a gay child and believe that gay people should not be allowed to work with children.55 In a 2018 study, over 80% of LGBTI+ persons reported having experienced some form of abuse by family members.56

Hate speech and hate crime are widespread but vastly underreported, both because hate crimes are improperly qualified and because victims are unwilling to refer incidents to the police due to stigma and fear of their response. There is a general sense of impunity for hate speech in Georgia, and the legislative framework fails to explicitly prohibit hatred based on sexual orientation or gender identity.57

Women’s rights and gender equality

Social attitudes towards women’s rights and gender equality reveal persistent patriarchal worldviews. A nationwide study conducted by the Caucasus Research Resource Center found that most respondents believed that women should accept lower pay and devote more time to their families than men. Additionally, the majority of respondents believed that men should have the final say in family decisions and that childcare is solely the mother’s responsibility. While few respondents believed that there are acceptable circumstances to hit a spouse, every fourth person considered that violence between a husband and wife is a private matter.58

These social attitudes are reflected in the realities of sexual and gender-based violence and the lack of adequate state responses. Femicides continue to be a problem in Georgia with dozens of cases reported each year. According to the Prosecutor’s Office, 186 women were killed between 2016 and 2022.59 Georgian criminal law regarding sexual violence does not align with international human rights law, including the Council of Europe Istanbul Convention. In particular, the provisions on rape and related offenses are not based on the absence of free and voluntary consent but rather require proof of physical force, threats, or the victimʼs helpless condition.60 Domestic violence legislation also fails to cover violence by non-cohabitating intimate partners.

As part of a broader push towards anti-equality policies, gender-related terminology and gender equality principles were removed from over a dozen laws in April 2025.61 The coordinating mechanism on equality issues envisaged in the 2014 Law on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination has never been established.62 Existing mechanisms, such as the parliament’s Council for Gender Equality and the government’s Commission on Gender Equality and Domestic Violence, were abolished or suspended in 2024.63

In Georgia, pregnant women face several barriers to accessing safe and legal abortions, including mandatory ultrasounds, long waiting periods, and dissuasive counseling. In 2023, Georgia further restricted access through a ministerial decree meant to dissuade abortions, including a requirement to include a psychologist and social worker during mandatory counseling.64 Out of the 49 European countries and territories assessed in the 2025 European Abortion Policies Atlas, Georgia ranks 41st with a score of 40.6%, which is a substantial decrease from its 58% Atlas score in 2021.65

Treatment of religious minorities

Muslims in certain regions face high degrees of hostility, discrimination, and violence. In the Adigeni municipality, Muslim worshippers who had gathered for prayer were repeatedly attacked and harassed in 2023–2024 by large groups of local residents led by local GOC clergy. No investigations were initiated by the local authorities and state officials pressured the local Muslim community to stop religious activities – which the local mufti agreed to on 10 April 2024.66 Meanwhile, the Muslim community in Batumi has been unable to construct a new mosque, forcing them to pray outside. The discriminatory refusal to grant a permit by Batumi City Hall was challenged by the Muslim community in 2017. It was overturned by the city court in 2019 and the court of appeal in 2021. However, a 2023 Supreme Court decision sent the case back to the court of appeal for reconsideration, where the case still remains unresolved.67

According to reports, there is a pattern of state authorities restricting the ability of religious minority communities to build new houses of worship by refusing to issue construction permits. Allegedly, local authorities are often taking into account the opinion of GOC clergy who disagree with the construction. At other times, state authorities have set extra-legal requirements for construction that hinders applicants from obtaining permits.68

A 2021 leak revealed that the State Security Service illegally wiretapped and surveilled representatives of religious organizations. However, no charges have since been filed with the Prosecutor Office and the investigation into the matter has been considered ineffective.69

Freedom of expression and advocacy of humanist rights

Standing up for humanist values, including human rights and democracy, has become increasingly difficult in Georgia. A range of legislative changes restrict freedom of expression, threaten civil society funding, challenge media independence, and criminalize peaceful protest. Meanwhile, mass protests following the 2024 election were met with police violence, torture, and imprisonment.

Freedom of association and civic space

Against a backdrop of intense public protests, the Georgian Dream governing party pushed through a number of laws in 2024 and 2025 that severely restrict the right to freedom of association and undermine civil society. The first notable law was the Law on Transparency in Foreign Influence, enacted in May 2024, which obliges non-profit organizations and media outlets that receive more than 20% of their funding from abroad to register as “organizations serving the interests of a foreign power.”70 Those organizations need to comply with far-reaching reporting and oversight requirements and must hand over, upon request, any information, including sensitive personal information. Failure to comply can be punished with administrative fines of up to GEL 25,000 (approx. USD 9,300).71 The law also affects non-GOC religious or belief organizations, since many of them are registered as non-profit legal entities, or operate affiliated charities, schools, or social-service organizations that are registered as non-profit entities.72 The Venice Commission found that the law violates international human rights law standards and creates a chilling effect for organizations by undermining their “financial stability and credibility.”73

In March 2025, the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) was adopted, which imposes far more restrictive obligations and individual criminal responsibility for violations. The FARA applies to individuals and both commercial and non-commercial organizations that engage in a broad range of vaguely defined “political activities” while acting under the influence of a “foreign principal,” a term that includes foreign organizations, citizens, and states.74 Anyone who falls within this broad definition must register as a “foreign agent,” submit detailed reports on their finances and activities to the authorities, share two copies of any public statement with the authorities within 48 hours, and label any disseminated material as made by a “foreign agent.”75 Non-compliance with the law can lead to fines of up to GEL 10,000 (approx. USD 3,700) and prison sentences of up to five years.76

Civil society groups also lament the stigmatizing impact that being labeled a “foreign agent” by these two laws has in the post-Soviet context. For instance, around the time of the adoption of the Transparency of Foreign Influence Law, NGOs were subjected to a disinformation and harassment campaign, including from politicians. Human rights defenders and activists received hundreds of threats, their offices and homes were vandalized with offensive inscriptions, and posters in several cities called specific activists and journalists “traitors” and “enemies.”77 From late April to June 2024, this escalated into violence with unidentified assailants attacking dozens of activists, frequently leading to hospitalization.78 Despite many attacks happening in public in front of witnesses and CCTV, no suspects have been identified or arrested.

The government also introduced amendments to the Law on Grants79 in April 2025, which obliges organizations to get consent from the government to receive grants from abroad. This was expanded in June 2025 to include even technical assistance and knowledge sharing. As part of the approval process, the government reviews the grant for compatibility with government programs and strategy. Shortly after the new law was put in place, the British Embassy released a statement saying it had halted all grant-making.80 Reception of a grant without approval can result in a fine on the recipient of twice the value of the grant. The ability of a civil society organization to solicit, receive and use funding is a fundamental part of the right to freedom of association.

Since the government introduced these legislative changes, state authorities have begun to prosecute prominent NGOs that had supported the 2024 protests. Starting in May 2025, the bank accounts of a dozen prominent NGOs have been frozen and staff members’ homes have been searched as part of an investigation into the alleged facilitation of group violence during the anti-government protests.81 At least eight leading CSOs received a court order requesting large amounts of documents in June 2025, including confidential information on survivors of human rights violations.82

It should also be noted that Georgian Dream officials have reportedly said that they would seek to ban the main opposition party. They have already simplified the process of prohibiting political parties and, therefore, have made it easier to ban politicians from standing for elections. Additionally, there have been reports that they have begun investigating the opposition for alleged crimes.83

Freedom of the press

Legislative changes passed in 2025 to broadcasting laws give the government editorial control and the ability to restrict funding. Changes to the Law on Broadcasting84 explicitly prohibit the receipt of foreign funding and in-kind assistance by broadcasters. Other media outlets are affected by the consent requirement for foreign funding of the previously-mentioned Law on Grants as well as by the onerous and stigmatizing registration and reporting requirements of FARA and the Law on Transparency of Foreign Influence.85 The amended Law on Broadcasting also ended self-regulation and imposed new coverage standards, including vague notions of “fairness and impartiality,” which are said to allow for arbitrary interpretation and enable editorial control by the government.86 A violation may escalate to the suspension or revocation of the broadcasting license. The Communications Commission that enforces the law has repeatedly been accused of selective enforcement against government-critical outlets and interference in their operations.87 The parliament also adopted legislative amendments to ban journalists from filming in court houses and to restrict their ability to scrutinize parliamentarians in 2025 and 2023 respectively.88

The ruling Georgian Dream party has already filed lawsuits against three opposition-aligned TV channels under the new law, and one channel has shut since.89 The anti-corruption bureau opened investigations into at least six outlets. Meanwhile, the government’s control over the Georgian Public Broadcaster has increased to such an extent – including through the dismissal of critical journalists – that, according to Reporters Without Borders (RSF), it “has become a mouthpiece for the ruling party.”90

The number of direct attacks on the press has also significantly increased. Between October 2024 and October 2025, RSF documented 600 attacks, including 127 violent assaults, by the authorities.91 Another Georgian NGO counted 108 violations of press rights between November 2024 and February 2025.92 The violence against media representatives is also fueled by incendiary statements from Georgian Dream politicians and impunity for attacks committed against journalists.93 Often using recently ratcheted and expanded offenses criminalizing a wide range of protest-related conduct, police are increasingly treating journalists as protesters and prosecuting them to obstruct coverage. Most prominently, Georgian journalist Mzia Amaghlobeli, founder of two independent media outlets, was recently sentenced to two years in prison for the crime of “attacking a police officer” – a sentence that human rights groups consider to be a politically motivated charge.94

Freedom of expression

A range of recent legislative amendments have made it easier to convict people – often for speech critical of government politicians. Although Georgia abolished criminal defamation in 2004, changes related to civil liability for defamation have eroded protections for the media and individuals facing lawsuits.95 Specifically, the recent legislative amendments have eliminated safeguards in favor of free speech, removed the damage requirement and public interest exception, reversed the burden of proof regarding whether a statement contains false facts, and eliminated protections for journalistic sources.96

In February 2025, a new offense of “insulting public officials, state and public servants” was introduced. The provision references “verbal abuse, swearing, persistent insults, and/or other offensive actions” without further definition. The OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) criticized the provision for being excessively broad, subjective, and liable for arbitrary interpretation.97 Offenses can be punishable with a fine of up to GEL 5,000 (approx. USD 1,800) or 60 days imprisonment. It should be noted that this offense also punishes insults directed at the leadership of legal entities under public law, which includes religious organizations and the GOC.

The onerous and stigmatizing registration and reporting requirements of FARA and the Law on Transparency of Foreign Influence has a chilling effect on civil society.. In addition, the aforementioned Law on the Protection of Family Values and Protection of Minors98 heavily restricts freedom of expression by effectively banning any public speech that could be deemed to “promote” LGBTI+ issues. Meanwhile, 2024 amendments to the Law on Public Service99 make it easier to dismiss civil servants for being critical of the government and large-scale dismissals have already taken place.100

Attempts to introduce a “blasphemy” law

In recent years, there have been several unsuccessful attempts to introduce a “blasphemy” law in Georgia, including in 2013, 2015, 2018, and 2024. In 2015, a draft law, advanced by the GOC, sought to penalize “insulting religious feelings” with the intent of protecting the GOC and its clergy from criticism. The draft proposed to introduce fines of up to GEL 600 (approx. USD 220) for repeat offenses.101 In 2018, MP Emzar Kvitsiani submitted a bill that would make “public manifestations of hatred” against religious symbols, organizations, clergy, and, believers – as well as the publication of materials with “the aim of offending religious feelings” – a criminal offense with imprisonment of up to one year.102 In January 2024, the Georgian Dream chairperson of the Legal Committee, Henri Okhanashvili, announced his intention to introduce legislation criminalizing the desecration of religious buildings and objects, which raised civil society concerns about the potentially vague and subjective nature of any offense.103

Freedom of peaceful assembly and crackdowns on protests

The crackdowns on public demonstrations in recent years, particularly during the post-2024 election protests, have been marked by violence and arrests. Police regularly used excessive force – including arbitrarily firing crowd control weapons, group beatings, and the alleged use of torture – against protesters and journalists.104 Particularly in the context of the 2024 protest, informal groups that are affiliated with the Georgian Dream government (“Titushkas”) have regularly intimidated and assaulted journalists, activists, and protesters – often in coordination with police and without facing legal consequences. Instead, police have arrested hundreds of largely-peaceful protesters on spurious charges and courts have imposed fines and prison sentences after perfunctory trials. As of February 2025, more than 60 protesters faced criminal charges.105

In February 2025, the parliament adopted a range of amendments to mete out harsher punishments for a swath of protest-related offenses while creating several new offenses. Next to amplifying fines and quadrupling the maximum detention period for administrative offenses from 15 to 60 days, jail sentences have been introduced for many offenses. Wearing a face mask, blocking a road intentionally, or possessing fireworks during a protest will result in a 15-day administrative detention for a first offense and jail time of up to two years for repeated offenses.106 OSCE-ODIHR raised serious concerns about the amendments’ compliance with international human rights law and characterized the penalties as “disproportionate” and creating a “chilling effect.”107

- Marina Nord et al., Democracy Report 2025: 25 Years of Autocratization – Democracy Trumped? (University of Gothenburg: V-Dem Institute, n.d.) accessed 8 December 2025, https://v-dem.net/documents/54/v-dem_dr_2025_lowres_v1.pdf; “Georgia” chapter in World Report 2025 (Human Rights Watch, 2025), https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2025/country-chapters/georgia; Georgian Young Lawyers’ Association, Laws against Speech: An Analysis of Legislative Restrictions on Freedom of Expression and Media Activity in Georgia (Tbilisi, 2025) https://gyla.ge/en/post/Kanoni-sitkvis-tsinaagmdeg-sais-kvleva-gamokhatvistavisupleba.[↩]

- Marina Nord et al., Democracy Report 2025: 25 Years of Autocratization – Democracy Trumped? (University of Gothenburg: V-Dem Institute, n.d.), accessed 8 December 2025, https://v-dem.net/documents/54/v-dem_dr_2025_lowres_v1.pdf[↩]

- Georgia v. Russia (II), No. 38263/08 (ECtHR [GC] January 21, 2021), https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng?i=001-207757 [↩]

- Dato Parulava, “Georgia Hits Brakes on EU Accession Bid,” Politico Europe, 28 November 2024, https://www.politico.eu/article/georgia-pause-eu-accession-bid-until-2028-irakli-kobakhidze/; Dato Parulava, “Georgia’s EU accession halted as country ‘has gone backwards’,” Politico Europe, 30 October 30, 2024, https://www.politico.eu/article/georgia-eu-accession-pause-reform-election-2024/ [↩]

- National Statistics Office of Georgia, “2014 General Population Census Results – Population by Regions and Religion,” (Geostat, 2024), https://www.geostat.ge/en/modules/categories/739/demographic-and-social-characteristics [↩]

- Constitution of Georgia, No 2071 of 23 March 2018 (1995), https://matsne.gov.ge/en/document/view/30346?publication=36 [↩]

- Venice Commission, Draft Opinion on the Draft Revised Constitution of Georgia as Adopted in the Second Reading on 23 June 2017, CDL-PI(2017)006-e (Council of Europe, 2017), para. 39, https://venice.coe.int/webforms/documents/?pdf=CDL-PI(2017)006-e [↩]

- Ekaterine Chitanava and Mariam Gavtadze, “Limitations to Freedom of Religion or Belief in Georgia: Legislation and State Policy,” Religion & Human Rights 15, nos. 1–2 (2020): 158–59, https://doi.org/10.1163/18710328-BJA10006 [↩]

- Constitution of Georgia, No 2071 of 23 March 2018 (1995), https://matsne.gov.ge/en/document/view/30346?publication=36; State of Georgia and the Apostolic Autocephalous Orthodox Church of Georgia, Constitutional Agreement between the State of Georgia and the Apostolic Autocephalous Orthodox Church of Georgia, 14 October 2002, https://matsne.gov.ge/en/document/view/41626 (English), https://matsne.gov.ge/ka/document/view/41626 (Georgian), (accessed 30 January 2026)[↩]

- Constitutional Agreement between State of Georgia and Georgian Apostolic Autocephaly Orthodox Church (“Concordat”) (2002), https://forbcaucausus.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/concordat.pdf [↩]

- ”Georgia” chapter in 2023 Report on International Religious Freedom (US Department of State, 2024) https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-report-on-international-religious-freedom/georgia/ [↩]

- ”Georgia” chapter in 2023 Report on International Religious Freedom (US Department of State, 2024) https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-report-on-international-religious-freedom/georgia/ [↩]

- Human Rights and Religious Organizations Coalition, Ethnic and Religious Minorities Rights Condition in Georgia, Joint Stakeholders’ submission to the UPR of Georgia (2020), para. 59, https://upr-info.org/sites/default/files/documents/2020-11/joint_submission_-_ethnic_and_religious_minorities_rights_condition_in_georgia.pdf; Ekaterine Chitanava and Mariam Gavtadze, “Limitations to Freedom of Religion or Belief in Georgia: Legislation and State Policy,” Religion & Human Rights 15, nos. 1–2 (2020), https://doi.org/10.1163/18710328-BJA10006; Ekaterine Skhiladze, The State of Right of Equality in Georgia 2024 (Coalition for Equality, 2025) https://equality.ge/en/9459 [↩]

- Tolerance and Diversity Institute, Freedom of Religion and Belief in Georgia: 2024 Report, https://tdi.ge/sites/default/files/tdis_forb_report_2024_eng.pdf; ”Georgia” chapter in 2023 Report on International Religious Freedom (US Department of State, 2024) https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-report-on-international-religious-freedom/georgia/ [↩]

- Tolerance and Diversity Institute, Freedom of Religion and Belief in Georgia: 2024 Report, https://tdi.ge/sites/default/files/tdis_forb_report_2024_eng.pdf [↩]

- Ekaterine Chitanava and Mariam Gavtadze, “Limitations to Freedom of Religion or Belief in Georgia: Legislation and State Policy,” Religion & Human Rights 15, nos. 1–2 (2020) https://doi.org/10.1163/18710328-BJA10006; Tolerance and Diversity Institute, Freedom of Religion and Belief in Georgia: 2024 Report, https://tdi.ge/sites/default/files/tdis_forb_report_2024_eng.pdf; ”Georgia” chapter in 2023 Report on International Religious Freedom (US Department of State, 2024) https://www.state.gov/reports/2023-report-on-international-religious-freedom/georgia/; Human Rights and Religious Organizations Coalition, Ethnic and Religious Minorities Rights Condition in Georgia, Joint Stakeholders’ submission to the UPR of Georgia (2020), para. 59, https://upr-info.org/sites/default/files/documents/2020-11/joint_submission_-_ethnic_and_religious_minorities_rights_condition_in_georgia.pdf [↩]

- European Council, Document: GEO-BO-01001 https://www.consilium.europa.eu/prado/en/GEO-BO-01001/index.html [↩]

- Parliament of Georgia, Law of Georgia on General Education, No. 1330, 8 April 2005, https://matsne.gov.ge/en/document/view/29248 (English), https://matsne.gov.ge/ka/document/view/29248 (Georgian), (accessed 30 January 2026)[↩]

- Pınar Köksal et al., “Religious Revival and Deprivatization in Post-Soviet Georgia: Reculturation of Orthodox Christianity and Deculturation of Islam,” Politics and Religion 12, no. 02 (2019): 15, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048318000585 [↩]

- Köksal et al., “Religious Revival and Deprivatization in Post-Soviet Georgia,” 15; “The Violation of the Principle of Religious Neutrality in the Tsalka Public School Requires the State to Take Positive Measures,” Social Justice Center, 29 February, 2024, https://socialjustice.org.ge/en/products/tsalkis-sajaro-skolashi-religiuri-neitralitetis-printsipis-darghvevis-fakti-sakhelmtsifosgan-pozitiuri-zomebis-mighebas-sachiroebs; Ketevan Gurchiani, “Georgia In-between: Religion in Public Schools,” Nationalities Papers 45, no. 6 (2017): 1100–1117, https://doi.org/10.1080/00905992.2017.1305346; Tolerance and Diversity Institute and Forum 18, Georgia UPR Submission (2020), para. 46, https://upr-info.org/sites/default/files/documents/2021-08/js13_upr37_geo_e_main.pdf [↩]

- HRCttee, Concluding Observations on the Fifth Periodic Report of Georgia, CCPR/C/GEO/CO/5 (Human Rights Committee, 2022), para. 41, https://undocs.org/CCPR/C/GEO/CO/5 [↩]

- Tolerance and Diversity Institute and Forum 18, Georgia UPR Submission, para. 47, https://upr-info.org/sites/default/files/documents/2021-08/js13_upr37_geo_e_main.pdf [↩]

- Tolerance and Diversity Institute, Freedom of Religion and Belief in Georgia: 2024 Report, https://tdi.ge/sites/default/files/tdis_forb_report_2024_eng.pdf [↩]

- “88.8% of Students Are Enrolled in Public Schools,” Georgian Business Consulting, 2 December , 2025, https://www.gbc.ge/en/news/Economics-news/888-of-students-are-enrolled-in-public-schools [↩]

- “GD Pumps GEL 43 Million into Orthodox Patriarchate Schools,” Civil Georgia, 21 March, 2025, https://civil.ge/archives/671007 [↩]

- Archil Gegeshidze and Mikheil Mirziashvili, The Orthodox Church in Georgia’s Changing Society (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2021), https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2021/07/the-orthodox-church-in-georgias-changing-society?lang=en [↩]

- Amnesty International, Georgia: Authorities Must Ensure Prompt and Effective Investigation into Allegation of Abuse of Children in Orthodox Church-Run Boarding School, Public statement EUR 56/4348/2021 (2021) https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/eur56/4348/2021/en/ [↩]

- “Georgia Failed to Protect Children against Violence and Abuse in Church-Run Orphanage, UN Committee Finds,” OHCHR, 27 June 27, 2024, https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2024/06/georgia-failed-protect-children-against-violence-and-abuse-church-run; N.M. and Others v. Georgia (Communicated), No. 16764/23 (ECtHR February 20, 2024), https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng?i=001-231655 [↩]

- CRC, Concluding Observations on the Combined Fifth and Sixth Periodic Reports of Georgia, CRC/C/GEO/CO/5-6 (Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2024), para. 27(b), https://undocs.org/CRC/C/GEO/CO/5-6 [↩]

- CEDAW, Concluding Observations on the Sixth Periodic Report of Georgia, CEDAW/C/GEO/CO/6 (Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, 2023), para. 43(a), https://undocs.org/CEDAW/C/GEO/CO/6 [↩]

- The Advocates for Human Rights and Anti-Violence Network of Georgia, Georgia’s Compliance with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights: Violence Against Women, 135th Session of the Human Rights Committee (2022), https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/15/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=INT%2FCCPR%2FCSS%2FGEO%2F48777&Lang=en [↩]

- CEDAW, Concluding Observations on the Sixth Periodic Report of Georgia, para. 43(a) https://undocs.org/CEDAW/C/GEO/CO/6 [↩]

- Archil Gegeshidze and Mikheil Mirziashvili, The Orthodox Church in Georgia’s Changing Society (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2021), https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2021/07/the-orthodox-church-in-georgias-changing-society?lang=en [↩]

- ISSP Research Group, “International Social Survey Programme: Religion IV – ISSP 2018,” version 2.1.0, with Johanna Muckenhuber et al., GESIS Data Archive, 2020, https://doi.org/10.4232/1.13629 [↩]

- Elene Dobordjginidze, “Speaker Calls on Voters to Support GD,” First Channel, 26 October 2024, https://1tv.ge/lang/en/news/speaker-calls-on-voters-to-support-gd/ [↩]

- Tolerance and Diversity Institute, Post-Election Environment: Freedom of Religion or Belief, Equality, and Secularity (Tbilisi, 2024), https://tdi.ge/sites/default/files/post-election_environment_forb_equality_and_secularity_26_oct_26_nov_2024_4.pdf; Tolerance and Diversity Institute, Freedom of Religion and Belief in Georgia: 2024 Report, https://tdi.ge/sites/default/files/tdis_forb_report_2024_eng.pdf [↩]

- Ekaterine Skhiladze, Eradication of LGBTQI+ Issues from State Policy: Challenges to Equality in Georgia (Women’s Initiatives Supporting Group, 2025), https://wisg.org/en/publication/320/Eradication-of-LGBTQI–Issues-from-State-Policy–Challenges-to-Equality-in-Georgia[↩]

- Ekaterine Skhiladze, The State of Right of Equality in Georgia 2024 (Coalition for Equality, 2025), https://equality.ge/en/9459 [↩]

- A.D. and Others v. Georgia, 57864/17, 79087/17, 55353/19 (ECtHR December 1, 2022), https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng?i=001-221237 [↩]

- ILGA World et al., State of Human Rights of LGBTI People in Georgia (2021 to 2025), https://equality.ge/en/9588[↩]

- Mariam Guliashvili, Report on LGBTQ+ Rights Violations in Georgia 2024, (Equality Movement, 2025) https://equality.ge/en/9481 [↩]

- Parliament of Georgia, Law of Georgia on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination, No. 2391-IIს, 2 May 2014, https://matsne.gov.ge/en/document/view/2339687 (English), https://matsne.gov.ge/ka/document/view/2339687 (Georgian), (accessed 30 January 2026)[↩]

- Ekaterine Skhiladze, The State of Right of Equality in Georgia 2024 (Coalition for Equality, 2025), https://equality.ge/en/9459 [↩]

- ILGA World et al., State of Human Rights of LGBTI People in Georgia (2021 to 2025), https://equality.ge/en/9588 [↩]

- Parliament of Georgia, Law of Georgia on Transparency of Foreign Influence, No. 4194-XIVმს-Xმპ, 28 May 2024, https://matsne.gov.ge/en/document/view/6171895 (English), https://matsne.gov.ge/ka/document/view/6171895 (Georgian), (accessed 30 January 2026)[↩]

- Parliament of Georgia, Law of Georgia Foreign Agents Registration Act, No. 399-IIმს-XIმპ, 1 April 2025, https://matsne.gov.ge/en/document/view/6461578 (English), https://matsne.gov.ge/ka/document/view/6461578 (Georgian), (accessed 30 January 2026)[↩]

- ILGA World et al., State of Human Rights of LGBTI People in Georgia (2021 to 2025), https://equality.ge/en/9588[↩]

- European Commission against Racism and Intolerance, ECRI Report on Georgia, sixth monitoring cycle (Council of Europe, 2023), para 35, https://rm.coe.int/sixth-report-on-georgia/1680ab9e64[↩]

- ILGA World et al., State of Human Rights of LGBTI People in Georgia (2021 to 2025), https://equality.ge/en/9588[↩]

- ILGA World et al., State of Human Rights of LGBTI People in Georgia (2021 to 2025), https://equality.ge/en/9588 [↩]

- Archil Gegeshidze and Mikheil Mirziashvili, The Orthodox Church in Georgia’s Changing Society (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2021), https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2021/07/the-orthodox-church-in-georgias-changing-society?lang=en [↩]

- European Commission against Racism and Intolerance, ECRI Report on Georgia, sixth monitoring cycle (Council of Europe, 2023), para 35, https://rm.coe.int/sixth-report-on-georgia/1680ab9e64 [↩]

- Amnesty International, Georgia: Authorities Must Ensure Prompt and Effective Investigation into Allegation of Abuse of Children in Orthodox Church-Run Boarding School., Public statement EUR 56/4348/2021 (2021) https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/eur56/4348/2021/en/ [↩]

- Independent Expert on protection against violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity, Visit to Georgia, A/HRC/41/45/Add.1 (UN Human Rights Council, 2019), https://undocs.org/A/HRC/41/45/Add Mariam Guliashvili, Report on LGBTQ+ Rights Violations in Georgia 2024, (Equality Movement, 2025), https://equality.ge/en/9481 [↩]

- Deboleena Rakshit and Ruti Levtov, Men, Women, and Gender Relations in Georgia: Public Perceptions and Attitudes, with Iago Katchkachishvili (UN Development Programme, 2020), https://www.undp.org/georgia/publications/men-women-and-gender-relations-georgia-public-perceptions-and-attitudes [↩]

- Independent Expert on protection against violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity, Visit to Georgia, A/HRC/41/45/Add.1 (UN Human Rights Council, 2019) https://undocs.org/A/HRC/41/45/Add[↩]

- Independent Expert on protection against violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity, Visit to Georgia, A/HRC/41/45/Add.1 (UN Human Rights Council, 2019) https://undocs.org/A/HRC/41/45/Add[↩]

- Caucasus Research Resource Center, Gender Equality Attitudes Study in Georgia, (CRRC, 2024) https://crrc.ge/en/report-gender-equality-attitudes-study-in-georgia/ [↩]

- Women’s Information Center and 28 other civil society organizations, Joint Shadow Report on the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (Georgia, 2023), 11, https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/15/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=INT%2FCEDAW%2FCSS%2FGEO%2F51129&Lang=en [↩]

- Equality Now and Sapari, Georgia: Addressing Violence and Discrimination against Women and Girls, Submission to the UPR of Georgia (2025), https://equalitynow.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/UPR-Georgia-Submission-by-Equality-Now-and-Sapari.pdf [↩]

- Equality Now and Sapari, Georgia: Addressing Violence and Discrimination against Women and Girls, Submission to the UPR of Georgia (2025), https://equalitynow.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/UPR-Georgia-Submission-by-Equality-Now-and-Sapari.pdf [↩]

- Ekaterine Skhiladze, The State of Right of Equality in Georgia 2024 (Coalition for Equality, 2025), https://equality.ge/en/9459 [↩]

- Equality Now and Sapari, Georgia: Addressing Violence and Discrimination against Women and Girls, Submission to the UPR of Georgia (2025), https://equalitynow.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/UPR-Georgia-Submission-by-Equality-Now-and-Sapari.pdf [↩]

- Anna Wallays et al., Rethinking Abortion Policy in Georgia: From Restrictive Measures to Evidence- Based Approaches, Position paper (Ghent University, 2024), https://www.ugent.be/anser/en/resources/anser-position-paper-rethinking-abortion-policy-in-georgia.pdf [↩]

- European Parliamentary Forum for Sexual and Reproductive Rights and International Planned Parenthood Federation, The European Abortion Policies Atlas (2021), https://www.epfweb.org/node/857; European Parliamentary Forum for Sexual and Reproductive Rights, European Abortion Policies Atlas 2025. https://www.epfweb.org/node/1156 [↩]

- Tolerance and Diversity Institute, Freedom of Religion and Belief in Georgia: 2024 Report, https://tdi.ge/sites/default/files/tdis_forb_report_2024_eng.pdf [↩]

- Tolerance and Diversity Institute, Freedom of Religion and Belief in Georgia: 2023 Report (2024), https://tdi.ge/sites/default/files/forb_in_georgia_2023_tdi.pdf [↩]

- Ekaterine Chitanava and Mariam Gavtadze, “Limitations to Freedom of Religion or Belief in Georgia: Legislation and State Policy,” Religion & Human Rights 15, nos. 1–2 (2020) https://doi.org/10.1163/18710328-BJA10006 [↩]

- Tolerance and Diversity Institute, Freedom of Religion and Belief in Georgia: 2024 Report, https://tdi.ge/sites/default/files/tdis_forb_report_2024_eng.pdf [↩]

- Amnesty International, The State of the World’s Human Rights, POL 10/8515/2025 (2025), https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/pol10/8515/2025/en/; “Georgia” chapter: Events of 2024,” in World Report 2025 (Human Rights Watch, 2025), https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2025/country-chapters/georgia; Georgian Young Lawyers’ Association et al., Georgia: Civil Society Organizations’ Joint Submission to the 51th Session of the UPR Working Group (2025), https://www.rights.ge/en/new/250[↩]

- “Georgia” chapter: Events of 2024,” in World Report 2025 (Human Rights Watch, 2025) [↩]

- Tolerance and Diversity Institute, Freedom of Religion and Belief in Georgia: 2024 Report, https://tdi.ge/sites/default/files/tdis_forb_report_2024_eng.pdf[↩]

- Venice Commission, Urgent Opinion on the Law of Georgia on Transparency of Foreign Influence, CDL-AD(2024)020-e (Council of Europe, 2024), paras. 96–97, https://www.venice.coe.int/webforms/documents/?pdf=CDL-AD(2024)020-e[↩]

- Georgian Young Lawyers’ Association, Laws against Speech: An Analysis of Legislative Restrictions on Freedom of Expression and Media Activity in Georgia (Tbilisi, 2025), https://gyla.ge/en/post/Kanoni-sitkvis-tsinaagmdeg-sais-kvleva-gamokhatvistavisupleba[↩]

- Georgian Young Lawyers’ Association, Laws against Speech: An Analysis of Legislative Restrictions on Freedom of Expression and Media Activity in Georgia (Tbilisi, 2025), https://gyla.ge/en/post/Kanoni-sitkvis-tsinaagmdeg-sais-kvleva-gamokhatvistavisupleba[↩]

- Human Rights Watch, Submission to the Universal Periodic Review of Georgia, 51st Session (Human Rights Watch, 2025) https://www.hrw.org/news/2025/07/23/submission-to-the-universal-periodic-review-of-georgia[↩]

- Ekaterine Skhiladze, The State of Right of Equality in Georgia 2024 (Coalition for Equality, 2025), https://equality.ge/en/9459, 10; Human Rights Watch, Submission to the Universal Periodic Review of Georgia, 51st Session (Human Rights Watch, 2025), https://www.hrw.org/news/2025/07/23/submission-to-the-universal-periodic-review-of-georgia[↩]

- Human Rights Watch, Submission to the Universal Periodic Review of Georgia, 51st Session (Human Rights Watch, 2025), https://www.hrw.org/news/2025/07/23/submission-to-the-universal-periodic-review-of-georgia[↩]

- Parliament of Georgia, Law of Georgia on Grants, No. 331, 28 June 1996, https://matsne.gov.ge/en/document/view/31510 (English), https://matsne.gov.ge/ka/document/view/31510 (Georgian), (accessed 30 January 2026) [↩]

- British Embassy Tbilisi, “The United Kingdom has tried, in good faith, to seek approval for several grants to Georgian civil society for voter education and citizen electoral monitoring, which the Central Election Commission confirmed are valuable activities…,” Facebook, June 11, 2025, https://www.facebook.com/ukingeorgia/posts/pfbid0U6nQEYWEZiHtaGRLFndfWZdYsvx73HKUMeoQwsEZm5vcpwNTZkDRJNFqFhqwHsv7l[↩]

- Mikheil Gvadzabia, “Georgian Authorities Freeze Accounts of Seven NGOs,” OC Media, 27 August, 2025, https://oc-media.org/georgian-authorities-freeze-accounts-of-seven-ngos/[↩]

- Human Rights Watch, Submission to the Universal Periodic Review of Georgia, 51st Session (Human Rights Watch, 2025), https://www.hrw.org/news/2025/07/23/submission-to-the-universal-periodic-review-of-georgia[↩]

- “The Legislative Changes That Have Shaped Georgia’s Authoritarian Slide,” OC Media, 30 October, 2025, https://oc-media.org/explainer-the-16-legislative-changes-that-have-shaped-georgias-authoritarian-slide/[↩]

- Parliament of Georgia, Law of Georgia on Broadcasting, No. 780, 23 December 2004, https://matsne.gov.ge/en/document/view/32866 (English), https://matsne.gov.ge/ka/document/view/32866 (Georgian), (accessed 30 January 2026) [↩]

- Georgian Young Lawyers’ Association, Laws against Speech: An Analysis of Legislative Restrictions on Freedom of Expression and Media Activity in Georgia (Tbilisi, 2025), https://gyla.ge/en/post/Kanoni-sitkvis-tsinaagmdeg-sais-kvleva-gamokhatvistavisupleba[↩]

- Georgian Young Lawyers’ Association, Laws against Speech: An Analysis of Legislative Restrictions on Freedom of Expression and Media Activity in Georgia (Tbilisi, 2025), https://gyla.ge/en/post/Kanoni-sitkvis-tsinaagmdeg-sais-kvleva-gamokhatvistavisupleba[↩]

- Georgian Young Lawyers’ Association, Laws against Speech: An Analysis of Legislative Restrictions on Freedom of Expression and Media Activity in Georgia (Tbilisi, 2025), https://gyla.ge/en/post/Kanoni-sitkvis-tsinaagmdeg-sais-kvleva-gamokhatvistavisupleba[↩]

- Georgian Young Lawyers’ Association, Laws against Speech: An Analysis of Legislative Restrictions on Freedom of Expression and Media Activity in Georgia (Tbilisi, 2025), https://gyla.ge/en/post/Kanoni-sitkvis-tsinaagmdeg-sais-kvleva-gamokhatvistavisupleba[↩]

- “The Legislative Changes That Have Shaped Georgia’s Authoritarian Slide,” OC Media, 30 October, 2025, https://oc-media.org/explainer-the-16-legislative-changes-that-have-shaped-georgias-authoritarian-slide/[↩]

- “Unprecedented Crackdown in Georgia: 600 Attacks against the Press in One Year,” Reporters Without Borders, 24 November, 2025, https://rsf.org/en/unprecedented-crackdown-georgia-600-attacks-against-press-one-year[↩]

- “Unprecedented Crackdown in Georgia: 600 Attacks against the Press in One Year,” Reporters Without Borders, 24 November, 2025, https://rsf.org/en/unprecedented-crackdown-georgia-600-attacks-against-press-one-year[↩]

- Georgian Young Lawyers’ Association et al., Georgia: Civil Society Organizations’ Joint Submission to the 51th Session of the UPR Working Group (2025), https://www.rights.ge/en/new/250[↩]

- Georgian Young Lawyers’ Association et al., Human Rights Crisis in Georgia Following the 2024 Parliamentary Elections (2025), https://rights.ge/en/new/247[↩]

- “Georgia: RSF Condemns the Sentencing of Mzia Amaghlobeli to Two Years in Prison Following a Biased Trial Marred by Irregularities,” Reporters Without Borders, 6 August, 2025, https://rsf.org/en/georgia-rsf-condemns-sentencing-mzia-amaghlobeli-two-years-prison-following-biased-trial-marred[↩]

- Human Rights Watch, Submission to the Universal Periodic Review of Georgia, 51st Session (Human Rights Watch, 2025), https://www.hrw.org/news/2025/07/23/submission-to-the-universal-periodic-review-of-georgia; Georgian Young Lawyers’ Association, Laws against Speech: An Analysis of Legislative Restrictions on Freedom of Expression and Media Activity in Georgia (Tbilisi, 2025), https://gyla.ge/en/post/Kanoni-sitkvis-tsinaagmdeg-sais-kvleva-gamokhatvistavisupleba[↩]

- Georgian Young Lawyers’ Association, Laws against Speech: An Analysis of Legislative Restrictions on Freedom of Expression and Media Activity in Georgia (Tbilisi, 2025), https://gyla.ge/en/post/Kanoni-sitkvis-tsinaagmdeg-sais-kvleva-gamokhatvistavisupleba[↩]

- OSCE-ODIHR, Georgia: Urgent Opinion on the Amendments to the Law on Assemblies and Demonstrations, the Code of Administrative Offences and the Criminal Code of Georgia (as Adopted on 6 February 2025), opinion FOPA-GEO/536/2025 [TN] (OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights, 2025), https://odihr.osce.org/odihr/587466[↩]

- Parliament of Georgia, Law of Georgia on the Protection of Family Values and Minors, No. 4437-XVIმს-Xმპ, 17 September 2024, https://matsne.gov.ge/en/document/view/6283110 (English version), https://matsne.gov.ge/ka/document/view/6283110 (Georgian), (accessed 30 January 2026) [↩]

- Parliament of Georgia, Law of Georgia on Public Service, No. 4346-Iს, 27 October 2015, https://matsne.gov.ge/en/document/view/3031098 (English), https://matsne.gov.ge/ka/document/view/3031098 (Georgian), (accessed 30 January 2026) [↩]

- Ekaterine Skhiladze, The State of Right of Equality in Georgia 2024 (Coalition for Equality, 2025), https://equality.ge/en/9459; Georgian Young Lawyers’ Association et al., Human Rights Crisis in Georgia Following the 2024 Parliamentary Elections (2025), https://rights.ge/en/new/247[↩]

- Amnesty International, Georgia: Draft Legislation on “Insulting Religious Feelings” Will Undermine Freedom of Expression, Public statement EUR 56/3387/2016 (2016), https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/eur56/3387/2016/en/[↩]

- “Lawmaker Proposes Criminal Liability for ‘Insult of Religious Feelings,’” Civil Georgia, April 26, 2018, https://old.civil.ge/eng/article.php?id=31046; “Georgian Parliament to Discuss Bill on ‘Insulting Religious Feelings,’” JAMnews, 24 April , 2018, https://jam-news.net/georgian-parliament-to-discuss-bill-on-insulting-religious-feelings/[↩]

- “Georgian Dream Plans to Toughen Penalties for Desecration of Shrines,” JAMnews, 11 January , 2024, https://jam-news.net/georgia-to-toughen-punishment-for-desecration-of-shrines/; “Social Justice Centre Responds to the Initiative to Criminalize Insult of Religious Buildings and Objects,” Social Justice Center, 12 January, 2024, https://socialjustice.org.ge/en/products/sotsialuri-samartlianobis-tsentri-religiuri-nagebobebisa-da-nivtebis-sheuratskhqofis-kriminalizebis-initsiativas-ekhmianeba[↩]

- Georgian Young Lawyers’ Association et al., Human Rights Crisis in Georgia Following the 2024 Parliamentary Elections (2025), https://rights.ge/en/new/247[↩]

- Georgian Young Lawyers’ Association et al., Georgia: Civil Society Organizations’ Joint Submission to the 51th Session of the UPR Working Group (2025), https://www.rights.ge/en/new/250[↩]

- “The Legislative Changes That Have Shaped Georgia’s Authoritarian Slide,” OC Media, 30 October, 2025, https://oc-media.org/explainer-the-16-legislative-changes-that-have-shaped-georgias-authoritarian-slide/[↩]

- OSCE-ODIHR, Georgia: Urgent Opinion on the Amendments to the Law on Assemblies and Demonstrations, the Code of Administrative Offences and the Criminal Code of Georgia (as Adopted on 6 February 2025), opinion FOPA-GEO/536/2025 [TN] (OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights, 2025), https://odihr.osce.org/odihr/587466[↩]